Inside Blued: China's Leading Gay Dating App Goes Global

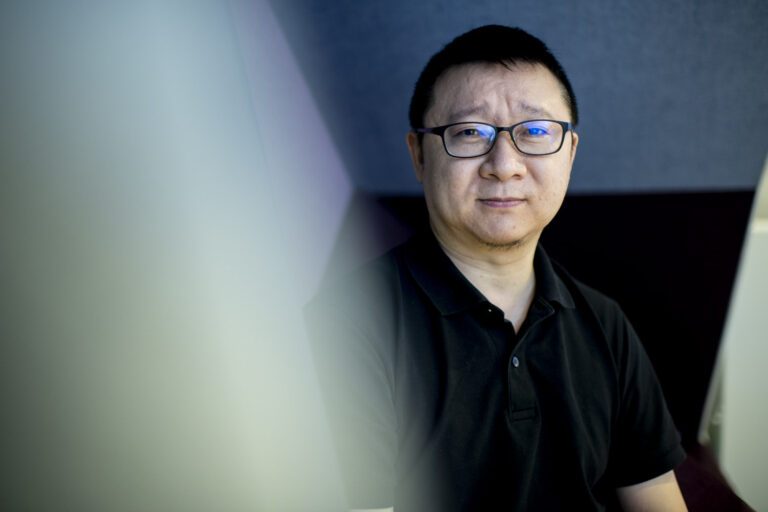

All things considered, Baoli Ma has led an unconventional life. Over the past two decades, Ma transformed himself from a closeted gay policeman into one of China’s foremost LGBT+ activists and tech entrepreneurs. And as far as Ma is concerned, he’s just getting started.

Born in 1977 in China’s Hebei province, Ma (also known by his pseudonym Geng Le) realised he was gay when he was 17. But entrenched cultural pressures and a lack of public acceptance kept him from coming out. On more reflective days, Ma would sit alone and wonder whether he was simply the “only weirdo in the world.”

When the internet boom hit China in 1998, Ma went looking for answers on local websites and social media platforms. But to his horror, he encountered a barrage of negative comments and retrograde portrayals of homosexual life.

Turning his attention beyond China’s borders, Ma researched a number of prominent international groups, including the World Health Organization and the American Psychological Association, and discovered an entirely different worldview than the one he had grown up with.

It dawned on Ma that homosexuality was accepted, if not celebrated, in a number of countries in the West. And more importantly: he wasn’t alone.

Ma resolved himself to helping others understand and accept their sexuality, launching the website “My Blue Memory” in 2000 in order to share personal stories and news about gay life.

The site gradually evolved into a charity known as Danlan Public Interest, which promotes greater awareness surrounding HIV and AIDS prevention. Meaning “light blue” in Chinese, Danlan references Ma’s hometown, the port city of Qinhuangdao.

“I wanted to tell other gay people in China that they are not sick and don’t need treatment,” he says, referring to conversion therapy, which was outlawed in China in 2014. “I also wanted to share scientific knowledge about homosexuality and encourage the public to accept the LGBT+ community.”

A Double Life

In order to protect his identity, career and fulfil familial expectations, Ma led an exhausting double life for over a decade. During the day Ma worked as a police officer; by night, he managed the charity website Danlan.org, answering several hundred messages a day and working until the early hours of the morning to keep up with inquiries.

Ma revealed that he was gay in a 2011 interview about his charity work with Sohu, an online publication in China. After the interview published, Ma received a flood of messages from friends asking him how and why he had suddenly become gay.

Although China decriminalised homosexuality in 1997 and later removed it from the official list of mental illnesses in 2001, the country still takes a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ approach. Effectively, this means that coming out remains a significant challenge for gay people since acceptance in Chinese society remains low.

The interview also complicated Ma’s professional life. His colleagues at the Public Security Bureau shunned him, while his supervisor forced him to choose between his job and the website. Ma chose the latter, and at the time he remembers thinking: “This is not about me but about the hundreds of thousands of netizens Danlan has helped.”

After resigning from the police force, Ma moved to Beijing to devote his time to LGBT+ advocacy. Luckily for him, mobile technology was just starting to take off and it was in this fertile environment that BlueCity was born in 2011.

Located in Chaoyang, a Beijing business district home to more than 3,600 national high-tech enterprises, the headquarters of BlueCity reflects the company’s youthful and inclusive spirit. Colourful cartoons and illustrations of people holding rainbow flags adorn the walls while meeting rooms are named after LGBT+ films, such as Happy Together, Beauty, and Lan Yu.

The office also provides gender-neutral toilets for LGBT+ team members, who make up more than half of the company’s 500-some employees. “In BlueCity, people can express their gender identity and sexuality freely, without the fear of being treated differently or jeopardising their careers.”

On the face of it, BlueCity is an internet technology company that focuses on serving the LGBT+ community around the world via apps, online health platforms and community action, such as working with relevant NGOs on HIV prevention.

Its best-known products include Blued, which debuted in 2012 as one of the first gay social network apps in China, while the company also runs several online healthcare and family planning platforms, such as Danlan Public Interest, He Health, and Bluedbaby.

When developing the dating app, Ma saw a unique opportunity, given that most of his LGBT+ friends struggled with English-language apps like Grindr or Hornet. “I want to help [gay people in China] find love,” he says. “With mobile, we can use our geolocation to connect with gay people nearby.”

When it launched in 2012, Blued ranked ninth on the App Store within the first week, according to the company. Like other gay dating apps, Blued enables users to connect and chat with potential dates, as well as livestream. Unlike other gay apps, however, it also provides healthcare and family planning services, in order to address the everyday needs of the LGBT+ population.

This July, BlueCity made history as the first gay social network to be publicly traded on the Nasdaq stock exchange, raising approximately US$85 million from its initial public offering.

One month later, the company announced the acquisition of LESDO – a social network provider launched in 2014 that serves the lesbian community in China – a move Ma describes as “a significant milestone … to serve subgroups within the broader LGBT+ community”.

“In China, the lesbian market is fragmented, with many small service providers lacking the ability to do sustainable product development or provide consistent services. LESDO represents a great opportunity for us to enter and consolidate the lesbian market,” he says.

Blued is currently available in 13 languages, and boasts 6.4 million monthly active users and more than 54 million registered users worldwide, attracting a loyal overseas following in markets like India, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam.

“I want to help gay people in China find love.”

Baoli Ma

Social responsibility

Shifting from an early focus on the ‘social’ in social media, Ma has expanded the company’s health and family planning services in recent years. In China, only infertile, heterosexual married couples can access assisted reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilisation or surrogacy. Therefore, many gay couples may look for help in other countries if and when they decide to have children.

To assist, BlueCity launched Bluedbaby in 2017, a platform dedicated to providing personalised family planning services for LGBT+ individuals. Working with several overseas associations, the website provides translation and consultation services to help individuals navigate foreign adoption and reproductive technology companies.

And last year, the team introduced He Health, a platform focusing on providing convenient and reliable online health services for men, such as HIV prevention, testing and advice regarding sexual dysfunction.

“We work with local government departments and NGOs to build these services. For instance, if you have any questions about AIDS, you can find out what treatments you need and what health services the government can provide through the app,” Ma explains.

Ma believes that online health services are particularly important for HIV-related medical needs. As of October 2019, 958,000 people had been infected with HIV in the country. Among the cases reported in the first ten months of 2019, roughly 74 per cent were infected through heterosexual contact and 23 per cent through homosexual contact, according to data released by National Health Commission of China.

“People living with HIV still face a lot of discrimination and stigmatisation, as many people still associate the disease with morality,” he says. “Our online medical consultations and drug sales can offer the professional service and confidentiality our clients need.”

According to Ma, one popular service is the online sale of PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) – a medicine that reduces the chance of being infected with HIV if taken within 72 hours after potential exposure. “We have partnered with local pharmacies to provide such services in many cities across China, including Beijing, Shanghai and Jinan. Within two hours of ordering, you will receive the medicine. This can truly help protect people’s health,” he says.

Across BlueCity’s platforms, the company counts more than 10 million page views of its HIV-related content. The Blued app also facilitated about 50,000 online appointments for HIV testing at more than 200 partnered testing establishments in China as of 2019.

Ma’s efforts to promote HIV awareness and prevention has received widespread recognition. In 2012, Ma was invited to meet then Chinese Vice-Premier Li Keqiang as a representative of a non-governmental organisation focusing on HIV prevention. In 2015, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Michel Sidibe visited the company and praised its work on HIV prevention.

However, the app has also met with criticism. According to a 2016 report by Caixin, a media group focusing on investigative journalism, Zhang Bei-chuan, a Chinese expert in HIV prevention and homosexuality, found in his study that many Blued users under 18 had falsely reported their age. Through the app, some young people had accessed pornographic content and engaged in illegal, and possibly unsafe, sex with adults.

In response, Ma tells Ariana: “Pornography and inappropriate content is a problem faced by many internet companies. To tackle this we have invested significant resources in developing advanced content monitoring technologies, policies and procedures, including an automated AI-enabled screening mechanism that automatically flags inappropriate or illegal content – such as pornography in forms of words, voices, photos and videos – as well as an anti-pornography and anti-spam mechanism in order to be more effective in preventing the dissemination of inappropriate information on the platform.”

He says the company also provides a “report” button for all users watching live. “When any inappropriate or illegal content is identified our team removes it. Further action may also be taken to hold relevant users accountable,” he says.

“I wanted to tell other gay people [in China] that they are not sick and don’t need treatment.”

Baoli Ma

Bright future

Although China has held a historically conservative stance on LGBT+ issues, Ma says acceptance of homosexuality has become more widespread in recent years. Media coverage, friendly policies, and greater visibility of homosexual people have reflected this shift – all of which leads to more openness and a better quality of life.

In December 2015, China saw its first gay-rights related case in court when Chinese nationals Sun Wenlin and Hu Mingliang sued the civil affairs bureau in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province.

The couple filed the lawsuit after an employee at the bureau rejected their application to get married, saying that same-sex marriage in China is not permitted. Although the Changsha court ruled against their case in April 2016, many gay rights activists are hopeful because it’s the first time a Chinese court agreed to hear such a lawsuit.

Meanwhile, a 2016 United Nations Development Programme survey entitled “Being LGBTI in China” highlighted the growing acceptance of the LGBT+ community in China, especially among the younger generation.

The survey interviewed more than 10,000 heterosexual people, mostly born after 1990, and found that over 70 per cent disagreed that homosexuality is a disease, while nearly 85 per cent supported the legalisation of same-sex marriage and the protection of LGBT+ rights.

However, in late 2015, the Chinese government banned homosexual content from appearing on television or online, alongside content dealing with incest, perversion, sexual assault, and sexual abuse.

Censorship also extends to literary works. In 2018, a female novelist in China, known by her online pseudonym Tianyi, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for writing and distributing a homoerotic novel, called Occupy. In a statement, police described the book as depicting “obscene sexual behavior between males” set to themes of “violence, abuse, and humiliation.”

When asked whether the increased crackdown on homosexual content has affected the operation of BlueCity’s online products, Ma explains: “As far as I know, the authorities removed some homosexual-related content from the internet because they contained erotic and sexual elements.” “Healthy” homosexual content that deals with love, rights, and healthcare, is still allowed to be published online.

Despite these setbacks, legal progress has been made. Since 2017, China has approved voluntary guardianship for all adults, which grants same-sex couples the right to appoint their partners as their guardian. This enables some of the same benefits conferred by marriage, including power of attorney, decision in medical treatments, and inheritance rights.

While netizens and members of the LGBT+ community view this decision as an important first step, many still long for the right to marry. Ma believes that with growing acceptance in Chinese society, as well as in neighbouring countries, the legalisation of same-sex marriage in China is not far off. “I think within 20 years, it could be possible.”

LGBT+ Rights in China

Same-sex marriage

China’s 1980 Marriage Law stipulates a woman’s right to choose her spouse (as opposed to arranged marriages), enables divorce and legalises the equality of men and women within a marriage. While the modified law better protects heterosexual women, it does not legally recognise same-sex marriage.

Discrimination protections

Within China’s legal framework, protection against LGBT+ discrimination is also absent. This means that if an LGBT+ individual experiences harassment, abuse or discrimination in any setting, they have no legal recourse.

Guardianship appointments

Under China’s voluntary guardianship system, all adults with full civil capacity and who are over 18 can appoint a guardian for their healthcare, property, funeral arrangements and general wellbeing should they become incapacitated. According to media reports, several gay couples in Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing have appointed each other as guardians.

Gender reassignment surgery

According to the Sex Reassignment Surgery Procedural Management Standard (2017 Edition) issued by the National Health Commission, those who want to undergo gender reassignment surgery must:

— Display a desire to undergo surgery for at least 5 years

— Undergo psychological treatment for at least 1 year

— Be diagnosed with “transsexualism”

— Be declared suitable for surgery

— Provide evidence that they’ve informed immediate family

— Be unmarried

— Be at least 20 years old

— Have no criminal record

— After the surgery, the individual can apply to change the gender on their identity documents.